Are you a Quiet Speculation member?

If not, now is a perfect time to join up! Our powerful tools, breaking-news analysis, and exclusive Discord channel will make sure you stay up to date and ahead of the curve.

I am writing this article on the eve of the v4 switchover. I don't know what the transition will bring to the market, but there is some good speculation in this thread on the forums.

Since I won't have a chance to respond to market developments this week, I thought it makes sense to take a step back and do a big picture article that looks at the fundamentals of Magic Online speculation and provides some tools for the future.

A wise man once said that it’s good to learn from our mistakes, but it’s even better to learn from other people’s mistakes. With that in mind, I canvassed a number of seasoned MTGO investors in the Quiet Speculation community to learn about what mistakes they had made in the past and what they had learned from them.

These folks gave me so much great material that I’m going to do a two-part series in which I highlight some of the key themes we can learn from. (Thanks to everyone who responded. If you don't see your feedback this week, check part two of the series in a couple weeks.)

Trying to Pick Winners Based on Intrinsic Power

This is a big one. One of the hardest things to do in Magic speculation is to identify specific cards that are undervalued. It’s hard enough to figure out which cards are good; it’s much harder to figure out which cards are better than the market thinks they are. The transaction costs on Magic online are low, the market is efficient, and the metagame is being refined by the hour.

Some of our worst mistakes occur when we think we know a card's intrinsic power better than the market does. The market is composed of tens of thousands of players playing millions of matches. It can be wrong and it can late...but more often then not it is right.

Sure, occasionally we’ll figure out that Sphinx's Revelation is a powerhouse rather than a role player. But for every Sphinx’s Revelation there will be many more Duskmantle Seer, Aurelia's Fury, and Advent of the Wurm. These cards--and many more--were touted as prime speculation opportunities but ended up as busts.

One example from my past was Bloodchief Ascension. Only one black mana, easy to turn on, and gives you such inevitability. I was sure they were underpriced at 2 tix each when Zendikar launched. Of course, I was terribly wrong, and they kept slipping until they were bulk.

We’ve probably all made this mistake. QS member maxiewawa writes cogently about it here:

"My major mistake would be trying to work out how good new cards are. I have tried and failed. The thing is that I'm not very good at Magic, and haven't ever tried to be good, not seriously at least. I used to think I was okay at it, but I've had to face facts. Usually when I try to pick good cards I fail, and when I get it right it's just a fluke. I've learned to give it up.

So I usually try to put my instinct to one side when it comes to new cards, and I just try to pick packs and cards that were successful at one time but for whatever reason are undervalued now (flashbacks, metagame change, out of season, prize structure etc).

On the other hand, I do like buying cheap cards that haven't proved but I always try to "hedge" with other cheap untested cards. By doing this I'm trying to acknowledge that I have no idea which cheapie is going to be popular, but statistically that some probably will."

- maxiewawa

Even experts can be wrong when picking cards. Go back through the archive of set reviews on StarCityGames, Channel Fireball, and other major sites and you will find smart and experienced players writing well-reasoned arguments about why certain cards were primed to go up. Only a fraction of them did.

The problem is that if you see something in a card, someone else has as well; that upside is usually priced into the market value from day one. Experts are fallible, and Quiet Speculation investors are no exception. As Koen writes:

"When I think of mistakes what first comes to mind is overcommitting on cards that were praised in the QS' articles, like Skaab Ruinator, Thragtusk in June, Aetherling..."

- Koen (koen_knx)

It's not that the experts followed bad reasoning. It's just that predicting correctly which cards will thrive requires getting a lot of things right--including complex and chaotic developments such as metagame shifts. And even Pro Tour players and seasoned speculators will often get it wrong.

Aaron Stuckert argues that when you hear the advice of experts you need to put things in perspective and come to your own conclusions:

"One thing I've learned is to never follow anyone's advice blindly, no matter how much you trust their opinion. Every time I've done that, I've been burned. You have to be able to understand and agree with their assessment, or else simply don't touch the spec. For example, I asked a friend of mine who was going to the PT to ship me any juicy tech for me to spec on. He tells me that in his testing, Ashiok, Nightmare Weaver has been an absolute house, and that I should go deep on those. So I buy a bunch at around 16 and they proceed to do nothing at the PT and freefall to around 6, where they still sit."

- "Acceptable Losses" (@Aaron_Stuckert)

Maybe some people in our community have gotten rich predicting which cards represent value from day one. But in my view, the secret to successful long-term speculation on MTGO is not being right in your individual predictions but instead being adept at reading market signals and understanding the cycles that drive card valuation.

Find what’s undervalued based on past performance rather than raw potential. This approach is less risky, more consistent, and can be just as profitable as “picking winners”.

Relying Too Much on Heuristics

This mistake is related to the one above. We see a pattern from the past and apply it, imperfectly, to a new card or cycle. Sometimes it works, but often it misses the mark. Charles Fey gives a great example:

"I took a hit recently on Underworld Cerberus. And to start, I want to compare Underworld Cerberus to Deathrite Shaman. Deathrite Shaman was one of my best buys ever--I want deep on it right away while it was super cheap and knew its intrinsic power without batting an eyelash. How? Simple: it cost one mana and had Tolstoy for a text box.

That's an easy heuristic, right? A low cost-to-text ratio more or less defines playability. It's a format based on bizarre, complicated things that happen for an incredible low cost, which is what Vintage and Legacy are built around. Even Brainstorm takes a while to explain for one blue mana: draw three and put two back, but not just two from the three you drew - any two. Tarmogoyf is a "vanilla" beater in a stale waffle cone of explanatory text.

The problem is I just didn't do the work. 'Cheap mythic that does a lot of stuff' is not a necessary or sufficient criteria for a card to go up. Why not? Well, for one thing, it was a fall set. For another, the gods pretty much made sure that when you look at the redemption-capped value of a given set, Underworld Cerberus was going to need more momentum than usual to succeed. And Cerberus sucks; it has a couple of strange effects that don't mean anything in a format when R/W Burn untaps on turn five and murders you with Warleader's Helix.

The lesson: simple heuristics can only do so much when you evaluate cards. 'Cheap mythics with big text boxes' is not a strategy and I should have given more thought to the obvious problems with a 6/6 five-drop that does precisely nothing the turn you play it except whimper plaintively at Desecration Demons overhead.

In any case, I have four foil copies available if you're playing the card in your Cerberus tribal deck. Cheap."

You’ve probably heard some of these heuristics: people will say it's a sure bet to speculate on “third set mythics,” “planeswalkers that can protect themselves,” or “real estate” (i.e. lands). There is some truth in these statements, but in the MTGO economy, being efficient or powerful is not enough. The MTGO ecosystem is a ruthless place, where only the “best in class” cards hold any value whatsoever. Everything else is pushed out to the bargain bin.

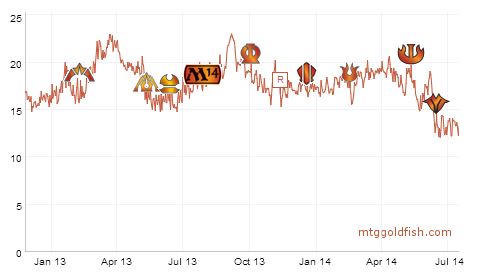

Another example of a faulty heuristic/analogue is Ravnica shocklands. People remembered that Zendikar fetchlands dropped down to 3-5 tix during their Standard run and then spiked to 10-30 tix once they became scarce. Many speculators predicted a similar (if muted) pattern with RTR block lands. Nothing seemed more certain than loading up on a broad basket of shocklands and watching them appreciate in value. At one point I had a couple hundred of these stashed away.

As we know, this strategy was not a big winner. A couple unexpected developments kept this spec from really popping.

First, Dragon’s Maze included all ten shocklands in a special slot, increasing supply. Then Theros brought with it devotion, a dominant strategy which, along with M14's Mutavault, pushed people toward mono-color decks and reduced demand for shocks.

Finally, it became clear that fetchlands--once considered the little brother to shocklands--were in far higher demand than shocks; not only were they used in greater quantities in Modern, they were also Legacy and Vintage staples.

So the analogue to fetchlands was imperfect. But even if it had been perfect there are no guarantees. In this case unexpected developments--the Dragon's Maze printing, the devotion mechanic, and the printing of Mutavault--conspired against to undermine this "perfect spec".

If you bought shocks at their floor you did just fine—most yielded a 20-40% profit in less than a year if you were able to sell near their peak. But this is a far cry from the 100-200% profit that many people had hoped for, and involved a lot of opportunity and transaction costs that might have been better applied elsewhere.

Swimming Upstream

The MTGO economy follows a set of predictable cycles based on releases, rotations, and redemptions. We will be diving deeper into these cycles in future articles.

These patterns provide investment opportunities that are safe and profitable. When you buy cards from a portfolio that has a depressed valuation you are “swimming downstream” and can let the flow of the Magic Online economy do the work for you. It's still possible to go astray, but your mistakes will be mitigated by market dynamics.

Sometimes we make investments that go against the general cycle of the MTGO economy—for example, buying cards in the summer that will rotate in the fall or buying cards during release events. These plays occasionally pay off, but they carry much greater intrinsic risk because they are “swimming upstream” against market trends.

Matt Lewis has been right more times than I can count, but he (and others) made a misreading of the market on Thragtusk. Here’s what he has to say about it one year later:

"Thragtusk was a big one. This card was a staple of Standard, and had fallen in price leading up to the release of DGM last year. Despite the price being 'low', and the card still being used, the price continued to fall into the summer and never recovered to its previous highs. It was a big loser.

Why did this happen?

a) Seasonal strength, prices are strong in the winter and less so in the summer.

b) Card was a rare, i.e. so no price floor supplied by redemption, when set prices fall, rares fall more than mythics.

c) Card was a core set rare. Core set is always played to some degree, so there's always new supply coming into the market (not sure how big of an effect this is).

d) 10-tix rares are in rarefied air, *ahem*. I don't go by hard and fast rules, but speccing on an in-print 10-tix rare is probably a mistake.As a comparison, I specced on Geist of Saint Traft for the exact same reasons, i.e. Standard staple and prices had fallen off a lot around a set release. This card ended up turning a small profit because it was mythic and so had an inherent price floor that Thragtusk did not."

KingSkyWing, who had a similar experience with the green beast, emphasizes the importance of focusing on market fundamentals:

"So I was one of those people last year who bought Thragtusks at 9 tix and sold them at 3 tix, waiting for the eventual "rebound", even as release of Magic 2014 is almost happening. The problem here is ignoring fundamentals. Fundamentally, rotation is coming and rotating cards that are not played in Eternal formats are going to be worth next to nothing. If you go against fundamentals, you're purely speculating, with odds usually not in your favor. If you can match your speculation with strong fundamentals, your speculation is also part investing. For example, if you buy a basket of played THS near-bulk rares (ex. Temples, Caryatid, Fleecemane, Anger, Nykthos, Soldier of the Pantheon, Chained to the Rocks, Boon Satyr, Firedrinker Satyr, Mistcutter Hydra, Swan Song, Fabled Hero, Prognostic Sphinx, Whip of Erebos) in the next month of two, they will almost assuredly be worth a lot more come Fall and Winter. Some of those cards probably will spike many thousand percents."

- KingSkyWing

What are some of the mistakes you've made that you've learned from? Put them in the comments below, or send me a direct message if you would like to have your thoughts included in the next installation...

-Alexander Carl (@thoughtlaced)

One of my big mistakes has been not realizing how slippery intrinsic value (or power of a card) is. A card can be a powerful play but if it doesn’t fit near perfectly into the format (whether standard, modern, or other) it is unlikely to be a home run spec. Often the difference between an all-star and a bench player is subtle and can only be discovered through the gauntlet of tournament results. I still enjoy putting money on unproven cards but understand I will make my share of mistakes.

Very well put. It’s hard for cards to make it thought the gauntlet, even when they’re powerful. These kinds of specs are fun, but generally low percentage.

I think the upstream/downstream metaphor is a good one, and KingSkyWing’s picks from Theros block are very solid. It’s hard to go wrong on a basket of playables that have the whole Fall and Winter to find their footing. I’d add Banishing Light to any list of cards that one should be accumulating. 3rd set uncommons have some pedigree and this card is a staple that won’t be competing with Detention Sphere in the Fall.

Great article. Keep up the good work!

Who is KingSkyWing..?

Scroll up, they are the last person referenced in the article.

Right, thanks!

I still think Underworld Cerberus can make a comeback. It really doesn’t suck. It sucks in a world full of Desecration Demons…but those are going away soon.

…yes Im biased because I was someone who went relatively deep on this guy. Now only hoping to make my money back! 😀

I don’t hate Underworld Cerberus either at the current price (0.40). It is very low risk as a Mythic–because of redemption it is basically at its floor. And while a breakout is unlikely, there’s always that possibility because it has a great rate and some nice abilities. So you could definitely do worse than picking up a few playsets for rotation.

There are no bad cards–just bad prices! Right now the price may be right for the triple headed hound.

That list has many rares. I learned from last year and rares are not safe bets.

Loxodon smiter, dreadbore,… They were all playabels that didn’t reach the goal

Yes, very good point. Rares on MTGO are quite different than in paper and follow different dynamics. We’ll discuss that in a future article.