Are you a Quiet Speculation member?

If not, now is a perfect time to join up! Our powerful tools, breaking-news analysis, and exclusive Discord channel will make sure you stay up to date and ahead of the curve.

It’s Modern Horizons spoiler season, and you’ve been carefully monitoring new cards in the set, eager to brew. Then the moment you’ve been waiting for arises: Slivers are confirmed in!

You rush to TCGPlayer to acquire that Sliver Queen you’ve been putting off purchasing. A 10% kickback from eBay or TCGPlayer would have been nice, but now that the ideas are flowing you are okay with that $80 price tag. You head to TCGPlayer.com, search for Sliver Queen, and find out that only a few copies are in stock with a $200 price tag.

You head to Card Kingdom’s site, but there’s no luck there.

How about Star City Games? Nope.

What is going on here?

A Sliver Queen Study

Last week I attempted to write an objective piece that covered the history and necessity of MTG finance. The fact that the game has an economy, consisting of varying rarities and power levels, was innate to Richard Garfield’s design. As soon as Black Lotus was printed to be better and rarer than Wall of Wood, relative values became a reality.

After completing the column, it occurred to me that my article was biased (though understandably so). I failed to address the dark side to MTG finance in the article. While I will always believe that the game’s economy is critical to the game’s success, I would be remiss not to point out the problems introduced by a concerted “MTG finance” community.

Before Slivers were originally spoiled in Modern Horizons, the number of copies in stock had already dwindled down to a couple dozen. But after the first Sliver was spoiled, the card quickly became unavailable everywhere. Shortly thereafter, copies started to trickle back into stock with price tags in excess of $200. In fact, the greediest sellers start with a ridiculously high price tag (there’s one seller on TCGPlayer with a $500 listing), and copies slowly enter the market from there.

This greed, this insistence on setting a new price five times higher than previous, and this sudden clearance of the internet, is what really gives MTG finance a deservedly bad reputation.

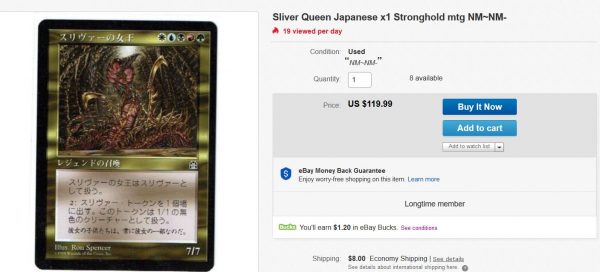

Then you get listings like these (and far worse)—they imply a speculator picked up whatever copies they could and threw them on eBay opportunistically, trying to cash out on the hype.

It’s possible this seller is a shop, and that shop happened to have eight copies in stock. But if I had to guess, I’d wager the seller scrambled to find whatever copies they could in reaction to the buyout, and now they’re trying to make a buck listing their copies on eBay at the new, elevated price. There used to be a bunch of $40-$50 Japanese Sliver Queens in stock. But when “MTG finance” cleans out copies at the old pricing, buying four or eight at a time, the sudden buyout enables the setting of a new, higher price.

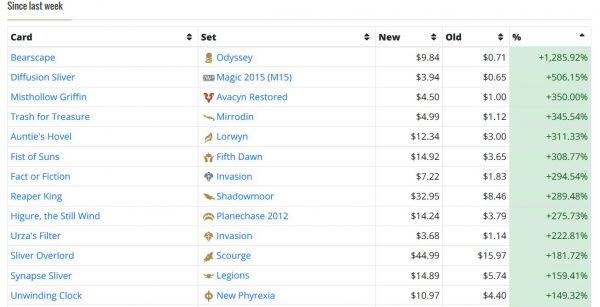

These instantaneous price-resets put MTG finance into a poor light. It happens all the time, and the buyouts really do become tiresome, especially to the casual player who doesn’t have time to watch the market like a hawk during spoiler season. And judging by the MTG Interests list from last week, it’s clear that MTG finance is both quick to react and incredibly thorough. Any synergy you could think of has already been targeted.

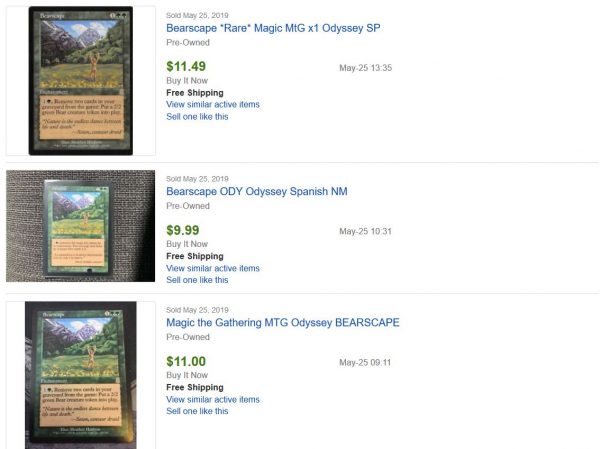

I mean, $10 for Bearscape?? Are you kidding me?!

MTG Finance: The Negatives

The MTG finance community may defend their actions and claim that their behavior only creates market inefficiencies in the very short term. If no one is willing to pay $500 for Sliver Queen, then no copies will exchange hands. New sellers will undercut that $500 price tag and the price will drop until a buyer is willing to pay up—that becomes the “market price”.

That’s a fine argument, and I agree that the correct equilibrium price will take hold…eventually. But I find some faults with the logic. Firstly, it’s unfair that the broader community has to wait to acquire their copies at a reasonable price. Of course, there aren’t enough Sliver Queens to go around, so not everyone can get a copy at a price they’re willing to pay. I won't believe for a minute that players need more than four copies of this card for their decks--most probably require only one. But by purchasing four to eight copies of the card at a time, it represents that many more players who can’t get a copy at a cheaper price. Maybe the price comes back down eventually, but this isn’t a guarantee.

That brings me to the second issue: emotions. MTG finance preys on emotionally driven and impulsive buyers. When someone sees new bears in Modern Horizons, they suddenly think of Bearscape. So they check TCGPlayer and see that Bearscapes are suddenly worth $10. If they’re patient, they could wait for the hype to subside and purchase their copies in a few weeks.

However, during spoiler season, many people are in a peak emotional state and are eager to brew with the new cards. That could lead them to make suboptimal purchasing decisions, such as buying their Bearscapes now at $10. This is how the MTG finance community profits by purchasing eight copies at a time at a buck a piece. Thus, the finance community takes advantage of peak emotional connections with Magic in conjunction with a temporary supply shortage. This is how the community can profit from buying out various cards.

The third concern I have with MTG finance behavior has to do with economic theory. When a card is bought out, supply slowly re-enters the market at lower and lower prices until buyers come along and make their purchase. This establishes the new price. The price is discovered in a manner akin to a Dutch Auction, an auction in which the auctioneer begins with a high asking price, and lowers it until some participant accepts the price. In other words, the buyer(s) willing to pay the most for the item ends up paying that much to make the purchase.

Contrast this to traditional eBay auctions, where an item’s price starts low and is bid on until no one is willing to pay more. The winning bidder is the person who was willing to pay the most for the item, and they end up paying the second highest bid plus some minimal increment. There’s a minor difference here I want to pause on.

In an eBay auction for a Magic card, the winning bidder essentially pays the amount the second highest bidder was willing to pay. In a Dutch auction, the winning bidder pays the highest amount they were willing to pay. See the difference? If everyone behaved rationally, there wouldn’t be much difference between the two approaches in terms of ending price. But during a period of peak emotions, I can’t help but wonder if there’s a difference in resulting price.

As a luxury good, there are some folks in the Magic community who can afford to pay up for the most desirable cards. If these people are in an emotional state, in a period of limited supply, and participating in a Dutch auction, I wonder if they’d end up overpaying for their cards. It’s just a theory I have—perhaps it’s an interesting topic for some prospective Ph.D. economist who also happens to play Magic!

Wrapping It Up: My Admission

Magic: the Gathering is a card game built upon an economy. There’s no way around this. Because money is involved, there will be greedy speculators who get involved in order to exploit the market’s inefficiencies. During spoiler season (or other periods of peak emotional interest), these inefficiencies magnify, yielding profitable opportunities.

Where there are opportunities, there are the opportunistic. They track the market closely, identify synergies, and purchase as many copies as they can at an “old price” in the hopes of selling into the hype at a new, higher (possibly inflated) price. This is an unfortunate facet to MTG finance, and it’s one that gives the finance community a poor reputation.

Throughout this article, I’ve been referring to that community as a third party unrelated to myself. But the reality is I have also participated in this speculative behavior—I am no less guilty than the next person. To deny this would be a blatant lie. However, I do tend to adhere to a couple personal rules.

- I never go very deep. If a card is under five bucks, I may buy 4-8 copies (rarely more). But if the card is pricier, I stick to a playset or less. I don’t want to tie up too much capital in a single card, but I also don’t like the idea of “buying out the market” because the resulting feel-bads of the rest of the community are something I empathize with.

- I don’t speculate on Old School cards. There are so many sweet, old cards I wish I could own. But I don’t have infinite resources. So why would I spend money to own more than four copies of an expensive Old School card when I could buy copies of other cards I don’t yet own. The only exception is Alpha Plague Rats, which I play in Alpha 40 and collect.

- I often don’t have the patience to play the “race to the bottom” game during buyouts. When Scrying Sheetss spiked recently, I managed to sell a couple on eBay. But I grew very tired of dropping my price one penny at a time to remain the cheapest copy for sale. Eventually, I gave up and cashed out to Card Kingdom’s buylist. In fact, buylisting is my favorite way to move cards during spikes because I don’t have to price compete and I don’t prey on others’ emotions.

- My speculation is always on the fringe of my activity. I estimate over 95 percent of my MTG resources are allocated to my decks and a modest collection of sweet Old School cards. I do speculate on occasion, but this activity is tiny relative to the rest of my collection. It’s the equivalent of owning $100,000 in an S&P 500 mutual fund for retirement and using $500 to trade in something like speculative Cannabis stocks and Bitcoin. I’m far too risk averse to do it any other way.

Even with these rules, I know I am part of the “problem”. But maybe I can slowly make up for this. In an upcoming article, I’m going to explore strategies to help you navigate an economy fueled by MTG finance. We’ll never see the end of MTG finance, but we can at least adopt strategies to help us avoid the pitfalls this community creates.

For now, I think that’s the best we can do.

Sigbits

- I noticed the return of a couple older cards to Card Kingdom’s hotlist. Gaea's Cradle, Shahrazad, and Transmute Artifact are three examples. They’re off their peaks, but maybe they are on their way back up. These three cards are buylisting for $220, $180, and $80, respectively.

- The Mythic Edition Jace, the Mind Sculptor is yet another version of this powerful Planeswalker that is on Card Kingdom’s hotlist. They currently offer $225 for this premium version of the card—I believe this reinforces that Jace is the most valuable Mythic Edition

- Grim Monolith and Sliver Queen are both buylisting near all-time highs now, both coincidentally at $105. I believe Grim Monolith’s buy price could climb even higher, but Sliver Queen’s may hit a momentary peak as the market floods with copies post-buyout.