Are you a Quiet Speculation member?

If not, now is a perfect time to join up! Our powerful tools, breaking-news analysis, and exclusive Discord channel will make sure you stay up to date and ahead of the curve.

One of the biggest questions to come out of GP Charlotte was the viability of Grixis Control. Although Patrick Chapin piloted his deck to a 9th place finish, there were no other Grixis Control representatives in the Top 32, and the deck itself made up just 1.9% of the Day 2 metagame. Chapin is also an excellent player in his own right, so it was hard to separate his skill from the deck he was piloting. Then came GP Copenhagen. Thiago Rodrigues may not have won with his own Grixis Control list, but his fifth place finish showed the deck was still a force to be reckoned with. But it was really the Copenhagen Day 2 metagame that removed any remaining doubt, with Grixis Control standing as the single most-played deck (Twin only beat it out as a supergroup). Grixis Control is here to stay in Modern, and with it comes a renewed focus on a certain kind of control philosophy: proactive control.

Proactive control is not new to Modern, but the recent success of Grixis Control has forced Modern players to reevaluate the importance of proactive strategies in our format. In this article, I discuss the differences between reactive and proactive control, arguing that proactive control is the way of the future in Modern. This approach, and the underlying reactive vs. proactive philosophy, will be helpful to both control mages who want to improve their deck, or to the average Modern player who wants to prepare for the months ahead.

[wp_ad_camp_1]

Historic Definitions of "Control"

In my GP Copenhagen retrospective yesterday, I talked a bit about this idea of reactive and proactive control. This generated some interesting questions in the comments, on forums, and via email, not to mention all the discussion around the issue not related to my article. This really is one of the enduring questions in Modern, which motivated me to explore the issue in greater depth today. And as with many of the "enduring question" articles, I want to start by defining some terms.

Before we can discuss the meanings of "reactive" and "proactive", we really need to begin with a definition of "control". It's particularly important here because that definition is where we first find this tension between reactive/proactive. Back in 2014, Reid Duke wrote a series of articles defining different constructed archetypes. In his article on "Control Decks", Duke described three of their characteristics:

- "Control decks are geared for the long game"

- "Control decks focus on shutting down the opponent"

- "[Control decks] win the game later, at their own convenience"

These definitions will ring true to most of us with constructed experience, especially those who played in the years before Modern (or played during many current Standard seasons). Control decks use countermagic, card draw, and removal to get to the late game. Then they win off some durable, efficient, but ultimately slow threat. This is the control archetype we remember from the days of Morphling and Psychatog, or even Dragonlord Ojuta from a more recent timeframe. But regardless of which old-school control we are looking at, we see the same theme through all the cards and in Duke's definition: "the long game". By its very nature, control is supposed to play for the marathon, not for the sprint. It doesn't try to win until the opponent is completely locked out of the game, and most of its cards are dedicated to establishing that sense of security. Moreover, its win conditions are at their best the longer the game goes. Playing Psychatog in turn 3 is a sure way to get the Atog killed. But play it on turn 12 after an Upheaval and with floating countermagic mana? That's the 30 year-old Scotch of control right there.

These definitions will ring true to most of us with constructed experience, especially those who played in the years before Modern (or played during many current Standard seasons). Control decks use countermagic, card draw, and removal to get to the late game. Then they win off some durable, efficient, but ultimately slow threat. This is the control archetype we remember from the days of Morphling and Psychatog, or even Dragonlord Ojuta from a more recent timeframe. But regardless of which old-school control we are looking at, we see the same theme through all the cards and in Duke's definition: "the long game". By its very nature, control is supposed to play for the marathon, not for the sprint. It doesn't try to win until the opponent is completely locked out of the game, and most of its cards are dedicated to establishing that sense of security. Moreover, its win conditions are at their best the longer the game goes. Playing Psychatog in turn 3 is a sure way to get the Atog killed. But play it on turn 12 after an Upheaval and with floating countermagic mana? That's the 30 year-old Scotch of control right there.

Reactive vs. Proactive Cards

It's this notion of the "long game" that creates the primary tension between reactive and proactive  elements, as well as reactive and proactive control decks more generally. By its very nature, control seems geared around "reactive" elements. As I define them, reactive elements (and, by extension, reactive control decks) seek to shut down opposing threats either after they are played (e.g. Terminate or Supreme Verdict, as they are played (e.g. Cryptic Command or Mana Leak), or even before they are played (e.g. Inquisition of Kozilek or Thoughtseize). The key here is not the timing of the card: in some sense of the word, discard is indeed "proactive" because it deals with a threat before that threat is deployed. Rather, the key is that reactive elements seek to answer threats, regardless of timing. In that sense, reactive elements are very much in line with Duke's points about control decks: they are focused on eliminating threats over the course of the game, not generating threats of their own.

elements, as well as reactive and proactive control decks more generally. By its very nature, control seems geared around "reactive" elements. As I define them, reactive elements (and, by extension, reactive control decks) seek to shut down opposing threats either after they are played (e.g. Terminate or Supreme Verdict, as they are played (e.g. Cryptic Command or Mana Leak), or even before they are played (e.g. Inquisition of Kozilek or Thoughtseize). The key here is not the timing of the card: in some sense of the word, discard is indeed "proactive" because it deals with a threat before that threat is deployed. Rather, the key is that reactive elements seek to answer threats, regardless of timing. In that sense, reactive elements are very much in line with Duke's points about control decks: they are focused on eliminating threats over the course of the game, not generating threats of their own.

Experienced control players will also note a second category of reactive elements, that of reactive threats. These are cards which win the game through either card advantage or damage, but can only be played when an opponent's own threats (and their answers to your threats) have been neutralized. Cards in this category include Elspeth, Sun's Champion and Celestial Colonnade. Sphinx's Revelation is another example of such a card, even if it doesn't directly win the game. These cards are not reactive in the sense that they answer a threat or address a dangerous board state. Rather, they are reactive in that they can only be safely played after your opponent's threats have been answered. This returns to Duke's point about control mages winning the game "at their own convenience", i.e. when the coast is clear. If you animate a Colonnade on turn 6 against your Twin opponent, you deserve to lose that game. Instead, you probably wait until turn 11 when you have mana for both Dispel and Cryptic Command.

That brings us to proactive elements and threats. Proactive elements are cards that develop your own  board state or gameplan, often cast at sorcery speed. Serum Visions is one of Modern's best proactive elements, but we can also find examples in cards like Farseek and Noble Hierarch. Proactive threats are cards that either put pressure and/or presence on the board (e.g. Tarmogoyf) or win the game outright (e.g. Scapeshift). This first category doesn't always have to be creatures. Vedalken Shackles is proactive, even if Kolaghan's Command has rendered the card unplayable. Blood Moon or Suppression Field can also fall in this category, especially if played against a deck that loses on the spot to either card. But for the most part, proactive threats take the form of a creature or a combo-win. Goyf may have been the go-to proactive threat of 2014 and earlier, but Tasigur, the Golden Fang and Gurmag Angler have been hogging the spotlight in more recent months. As for combo, it's all Twin all the time (with the occasional Scapeshift, as GP Copenhagen showed).

board state or gameplan, often cast at sorcery speed. Serum Visions is one of Modern's best proactive elements, but we can also find examples in cards like Farseek and Noble Hierarch. Proactive threats are cards that either put pressure and/or presence on the board (e.g. Tarmogoyf) or win the game outright (e.g. Scapeshift). This first category doesn't always have to be creatures. Vedalken Shackles is proactive, even if Kolaghan's Command has rendered the card unplayable. Blood Moon or Suppression Field can also fall in this category, especially if played against a deck that loses on the spot to either card. But for the most part, proactive threats take the form of a creature or a combo-win. Goyf may have been the go-to proactive threat of 2014 and earlier, but Tasigur, the Golden Fang and Gurmag Angler have been hogging the spotlight in more recent months. As for combo, it's all Twin all the time (with the occasional Scapeshift, as GP Copenhagen showed).

The big difference between proactive and reactive cards, especially proactive and reactive threats, is speed. Reactive threats are slow: you cast them late in the game after you can protect them and after an opponent is out of resources. Even if the reactive threat isn't that expensive (e.g. Psychatog), it's still played as an expensive, late-game card. Proactive threats are generally faster: you either cast these early and protect them, or you cast them as soon as possible if your opponent leaves an opening. Reactive threats obviously fit with control's historic focus on the long game. Proactive threats do not. Indeed, proactive threats are often associated with decks that either don't look like control or just aren't control at all. For years, UR Twin was branded as a combo deck, with Temur and Grixis Twin as tempo. The same was true of Scapeshift. Tarmogoyf was, at its slowest, a BGx midrange card. At its fastest, it was the workhorse of Zoo. Meanwhile, control mages were stuck on Esper Gifts, UWR Control, Cruel Control, and other overwhelmingly reactive strategies. Proactive threats seemed philosophically incompatible with these latter decks, and many Modern mages have taken this to heart in the years since.

The New Face of Modern Control

When Modern players look back on the history of control, they will view Fate Reforged as a turning point for the format's control decks. Although it took a few months and events for them to catch on, the delve creatures are the best thing to happen to Modern control since Snapcaster Mage. Snapcaster might still be the best card in control, and probably the best card in Modern, but without his delving friends, he wouldn't have viable control shells to empower. Here's Thiago Rodrigues's 5th place list from Copenhagen, a prime example of how control will look as Modern evolves:

Grixis Control, by Thiago Rodrigues (GP Copenhagen 2015, 5th place)

Rodrigues is by no means the first player to insert proactive threats into a predominantly reactive control shell. He's not even the first Grixis Control player to do it. But he was the highest-finishing Grixis Control player at Copenhagen, and it is Copenhagen more than any other event in the past few months that is going to put this proactive control on the map. As I mentioned in the article's opening, Grixis Control had a commanding 7.6% metagame share at the GP, a huge jump from Charlotte where it had a paltry 1.9%. This success is likely to incentivize more players to try out the lists and innovate their own, and we should expect to see lots of Grixis Control in the future.

Of course, the success of the archetype doesn't necessarily speak to those underlying tensions between proactive threats like Tasigur/Angler and a shell that is supposed to be reactive. Is it even fair to call this deck "Grixis Control" and not something like "Grixis Midrange" or "Grixis Tempo"? How can this deck be considered "control" when it's dropping a turn 2 Tasigur? Isn't that playline just too fast for a deck that is supposed to be playing "the long game"? These are all important questions to address, and common questions many control mages will ask. I want to start with the most important of the group: addressing whether or not this is actually a control deck. To do that, we need to return to our original definition of control that we borrowed from Duke's article.

Here are those initial three definitions again, this time applied to the Grixis Control list. With the exception of a single, bolded word in point #3, the definitions are unchanged. I also give a brief comment on how each definition is relevant to Grixis Control itself.

- "Control decks are geared for the long game"

For many players, the key term in this definition is "long game". But that's actually not the most important term for me. That honor belongs to "geared", which suggests the option to go to the long game, but not necessarily the need to go to the long game. If a game does go long, Grixis Control is totally fine. It has both Commands along with Snapcaster to generate incredible value and card advantage, as well as more than enough answers to address all of an opponent's threats as they are played. But that doesn't mean Grixis Control is slavishly committed to that long game. It just has the tools to go long if needed. That should also be considered true of any Modern control deck, not just Grixis.

For many players, the key term in this definition is "long game". But that's actually not the most important term for me. That honor belongs to "geared", which suggests the option to go to the long game, but not necessarily the need to go to the long game. If a game does go long, Grixis Control is totally fine. It has both Commands along with Snapcaster to generate incredible value and card advantage, as well as more than enough answers to address all of an opponent's threats as they are played. But that doesn't mean Grixis Control is slavishly committed to that long game. It just has the tools to go long if needed. That should also be considered true of any Modern control deck, not just Grixis.

- "Control decks focus on shutting down the opponent"

Grixis Control has five proactive threats (Tasigur/Angler) and two more reactive ones (Tar-Pit) to win the game. Compare that to the 22 ways it has of shutting down an opponent, which is actually at least 26 ways once you count in Snapcaster recursion (and more again when you consider Kolaghan's Command recursion of those Snapcasters). Just because Grixis Control players add in a handful of proactive threats, this doesn't mean the focus has shifted away from shutting down the opponent. Indeed, the overwhelming majority of cards in the deck couldn't be more focused on shutting down the opponent! Between countermagic, removal, bounce, and general board control, this deck is totally packed with shutdown mechanisms. The addition of five proactive threats doesn't detract from that focus: they are just supplements.

Grixis Control has five proactive threats (Tasigur/Angler) and two more reactive ones (Tar-Pit) to win the game. Compare that to the 22 ways it has of shutting down an opponent, which is actually at least 26 ways once you count in Snapcaster recursion (and more again when you consider Kolaghan's Command recursion of those Snapcasters). Just because Grixis Control players add in a handful of proactive threats, this doesn't mean the focus has shifted away from shutting down the opponent. Indeed, the overwhelming majority of cards in the deck couldn't be more focused on shutting down the opponent! Between countermagic, removal, bounce, and general board control, this deck is totally packed with shutdown mechanisms. The addition of five proactive threats doesn't detract from that focus: they are just supplements.

- "[Control decks] can win the game later, at their own convenience"

This is the only definition I want to modify from Duke's original article. It's not that Grixis Control, or Modern control more generally, wins the game later. It's that it can win the game later if it needs to. In some sense, this follows directly from the first point about how control decks are "geared" for the late game. Being geared for the late game doesn't need to mean helplessness in the early game, or an inability to close out the game before turn 13. It just means that this deck doesn't automatically lose once you get past turn 6. Grixis Control is able to keep that option open while still maintaining a core strategy of late game gearing and the more reactive, answer-every-threat focus. It would be a different story if the proactive threats were themselves preventing you from shutting down opposing threats. But Tasigur and Angler are cheap enough that they avoid this issue: you can easily drop one of them with mana up to shutdown a threat next turn. That is the essence of control, and both Tasigur and Angler play into that nicely.

This is the only definition I want to modify from Duke's original article. It's not that Grixis Control, or Modern control more generally, wins the game later. It's that it can win the game later if it needs to. In some sense, this follows directly from the first point about how control decks are "geared" for the late game. Being geared for the late game doesn't need to mean helplessness in the early game, or an inability to close out the game before turn 13. It just means that this deck doesn't automatically lose once you get past turn 6. Grixis Control is able to keep that option open while still maintaining a core strategy of late game gearing and the more reactive, answer-every-threat focus. It would be a different story if the proactive threats were themselves preventing you from shutting down opposing threats. But Tasigur and Angler are cheap enough that they avoid this issue: you can easily drop one of them with mana up to shutdown a threat next turn. That is the essence of control, and both Tasigur and Angler play into that nicely.

It's this third point which transitions us to the importance of proactive threats in the predominantly reactive shell. When you are stuck with purely reactive threats and elements, it's basically impossible to have the option of winning before the late game. But if you can add those threats while preserving your other elements, the only thing you are doing is increasing your range. You aren't actually compromising the core values of your deck. Moreover, the proactive threats are actually a form of answer in their own right! A giant 5/5 body on the board is effective removal for all sorts of small creatures. At worst, it's a multi-turn Fog that buys the control player time. At best, even if not in the red zone itself, it's a multi-turn removal spell that either kills multiple creatures or eats other removal spells and mana. To some extent, you want to be careful with your proactive threats and how they interact with removal. Control gains virtual card advantage in blanking opposing removal, and every body you add reduces that gain. But because Angler and Tasigur are already blanking so many spells (Decay, Bolt, Kolaghan's, Electrolyze, etc.), they don't really suffer from this drawback.

Why Reactive At All?

Before I wrap up, I want to address a question I have heard about Modern control decks. Many authors, myself included, have talked about Modern being a proactive format. It rewards proactive plays, cards, and decks: this is not a format where you want to durdle around and wait for your opponent to punch through your defenses. Moreover, Modern is a format where threats are often better than answers. We lack Legacy's catchall powerhouses like Force of Will and Wasteland, instead relying on answers that can feel relatively narrow in metagames clogged with diverse threats. If proactive threats are the way to go, then why bother with reactive elements at all? Why not just go pure proactive and leave control in the past?

There are two reasons we shouldn't completely abandon reactive elements in favor of purely proactive strategies. The first is the, oftentimes ignored, power of our reactive cards. Snapcaster, Cryptic, Kolaghan's, Terminate, Remand: these are some of the most powerful cards in Modern, even if they don't have quite the same catchall strength as similar police cards in Legacy. But when paired with bullets like Dispel and Spell Snare, these reactive answers can completely take over a game and shut down an opponent (which is the essence of control). The key is in pairing the strongest control spells in the format (other examples include Verdict, Damnation, Clique, etc.) with some of the narrower ones to compensate for holes.

There are two reasons we shouldn't completely abandon reactive elements in favor of purely proactive strategies. The first is the, oftentimes ignored, power of our reactive cards. Snapcaster, Cryptic, Kolaghan's, Terminate, Remand: these are some of the most powerful cards in Modern, even if they don't have quite the same catchall strength as similar police cards in Legacy. But when paired with bullets like Dispel and Spell Snare, these reactive answers can completely take over a game and shut down an opponent (which is the essence of control). The key is in pairing the strongest control spells in the format (other examples include Verdict, Damnation, Clique, etc.) with some of the narrower ones to compensate for holes.

This leads us to the second reason for the continued relevance of reactive elements: Modern's diverse metagame. If you commit yourself to a purely reactive or linear plan, you are gambling that a) you are faster and more focused than your opponents, b) you are more resilient than your opponents, and c) your opponents are unprepared for you. If your gamble pays off then hey, welcome to your new Amulet Bloom overlords in the Top 8! But when that gamble is miscalculated, or you just run into bad matchup luck, you can easily flop out of the tournament before Day 1 is even over. The catchall, reactive suite of cards like Snapcaster and the Commands give you a tremendous degree of versatility in all matchups, both those you expect (e.g. UR Twin, Affinity, Jund), and those you just happen to run into (e.g. Lantern Control, Death and Taxes, Living End). Only a proper control deck can leverage these reactive answers, ideally alongside their proactive gameplan.

Hopefully this article both drives you towards the reactive/proactive control mixes, and encourages you to brew some of your own. Whether with the delve creatures, Goyf, or even old-school fallbacks like Bitterblossom or Geist of Saint-Traft, you can easily combine proactive threats into your reactive gameplan to win games in Modern. This is likely to be the new face of control going forward, so expect to either play it or beat it in the months to come.

Suicide Shadow may not have won the event or even made Top 8, but it was still one of the most significant decks at GP Copenhagen. Why? Because while everyone else was packing Blood Moon for Amulet Bloom, Rest in Peace for Grishoalbrand, and Fulminator Mage for Tron, Anteri was mauling people with 15/15 battle-raging Shadows. It would have been impossible, and quite frankly, paranoid and stupid, to prepare for his deck. In that sense, Suicide Shadow underscores one of the most important lessons of Modern: there is always another linear deck out there. These outliers may not constitute a large metagame share and you may not even run into one of then at your next tournament (especially a big one). But rest assured that somewhere on the floor there's a guy playing his trusty tier 1 deck and getting flattened by Temur Battle Rage.

Suicide Shadow may not have won the event or even made Top 8, but it was still one of the most significant decks at GP Copenhagen. Why? Because while everyone else was packing Blood Moon for Amulet Bloom, Rest in Peace for Grishoalbrand, and Fulminator Mage for Tron, Anteri was mauling people with 15/15 battle-raging Shadows. It would have been impossible, and quite frankly, paranoid and stupid, to prepare for his deck. In that sense, Suicide Shadow underscores one of the most important lessons of Modern: there is always another linear deck out there. These outliers may not constitute a large metagame share and you may not even run into one of then at your next tournament (especially a big one). But rest assured that somewhere on the floor there's a guy playing his trusty tier 1 deck and getting flattened by Temur Battle Rage.

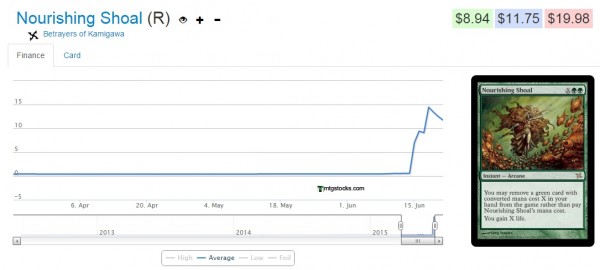

By UW Midrange I mean Kitchen Finks, Restoration Angel, and Celestial Colonnade. My opponent apparently worked with Jeff Hoogland on the list. Game 1, I keep a hand of 2 Bolts, Tarfire, Scour, and lands, and draw a third Bolt. My opponent’s turn 1 Colonnade lets me know this hand might not get me there. Neither of us do anything until I draw a Delver some turns later. Path to Exile targets him on my upkeep but I hardcast a Shoal for 1, then draw a Hooting Mandrills, attack a couple times, and burn my opponent out with Bolts. All he drew was a Kitchen Finks. Game 2, I resolve turn 3 Blood Moon after my opponent taps out for Finks, taking him off white. He eventually draws a second Island and transmutes Tolaria West for Plains, allowing him to flash in a Restoration Angel. But by then my Huntmaster’s flipped three times too many.

By UW Midrange I mean Kitchen Finks, Restoration Angel, and Celestial Colonnade. My opponent apparently worked with Jeff Hoogland on the list. Game 1, I keep a hand of 2 Bolts, Tarfire, Scour, and lands, and draw a third Bolt. My opponent’s turn 1 Colonnade lets me know this hand might not get me there. Neither of us do anything until I draw a Delver some turns later. Path to Exile targets him on my upkeep but I hardcast a Shoal for 1, then draw a Hooting Mandrills, attack a couple times, and burn my opponent out with Bolts. All he drew was a Kitchen Finks. Game 2, I resolve turn 3 Blood Moon after my opponent taps out for Finks, taking him off white. He eventually draws a second Island and transmutes Tolaria West for Plains, allowing him to flash in a Restoration Angel. But by then my Huntmaster’s flipped three times too many.

Game 1, I mulligan once and assemble an army of Goyfs and Mandrills. My opponent stalls just long enough to find Splinter Twin for the Exarch with Desolate Lighthouse at 6 life. Game 2, my turn 2 Mandrills goes unanswered. Probe gets Negated, and I Simic Charm pump with my opponent at 10. He goes to 3 and tries to Dispel my Lightning Bolt, but I respond with Stubborn Denial. Game 3, I mulligan once and am stuck on two lands with a hand of Bolt, Simic Charm, Destructive Revelry, Stubborn Denial, Serum Visions. I have Goyf and Mandrills in play when he goes off, and I try to Deny the Splinter Twin to play around Spell Snare since my opponent’s at just 4 life (no sense in maybe blowing him out with Charm). He taps out for Dispel and I’m short the third land to cast Revelry or Charm.

Game 1, I mulligan once and assemble an army of Goyfs and Mandrills. My opponent stalls just long enough to find Splinter Twin for the Exarch with Desolate Lighthouse at 6 life. Game 2, my turn 2 Mandrills goes unanswered. Probe gets Negated, and I Simic Charm pump with my opponent at 10. He goes to 3 and tries to Dispel my Lightning Bolt, but I respond with Stubborn Denial. Game 3, I mulligan once and am stuck on two lands with a hand of Bolt, Simic Charm, Destructive Revelry, Stubborn Denial, Serum Visions. I have Goyf and Mandrills in play when he goes off, and I try to Deny the Splinter Twin to play around Spell Snare since my opponent’s at just 4 life (no sense in maybe blowing him out with Charm). He taps out for Dispel and I’m short the third land to cast Revelry or Charm. Probe shows me double Signal Pest and an Arcbound Ravager. I Shoal the Ravager but the Pests, backed up by a Welding Jar, prove too much for my two flipped Delvers. A second Ravager puts a counter on Pest so it kills Aberration after blocks. Game 2, Tarfire into Shoal slows my opponent way down. A 6/7 Tarmogoyf puts him on a two-turn clock. He gets Cranial Plating on a Spellskite and attacks me, but I bounce the Skite with Simic Charm and Revelry the Plating. I bounce the Skite again next turn and attack for lethal. Game 3, I’m too slow to burn a Vault Skirge with Tarfire. I was waiting on a Huntmaster to eat the Skirge and taking 1 Lifelink and 1 Infect damage per turn. Couldn’t find a single threat of my own to establish an actual clock and Champion + Galvanic Blast killed me.

Probe shows me double Signal Pest and an Arcbound Ravager. I Shoal the Ravager but the Pests, backed up by a Welding Jar, prove too much for my two flipped Delvers. A second Ravager puts a counter on Pest so it kills Aberration after blocks. Game 2, Tarfire into Shoal slows my opponent way down. A 6/7 Tarmogoyf puts him on a two-turn clock. He gets Cranial Plating on a Spellskite and attacks me, but I bounce the Skite with Simic Charm and Revelry the Plating. I bounce the Skite again next turn and attack for lethal. Game 3, I’m too slow to burn a Vault Skirge with Tarfire. I was waiting on a Huntmaster to eat the Skirge and taking 1 Lifelink and 1 Infect damage per turn. Couldn’t find a single threat of my own to establish an actual clock and Champion + Galvanic Blast killed me. Game 1, we both mulligan and I lead with Probe, Delver. I see Dryad Arbor, Rancor, Daybreak Coronet, Spirit Link, Spirit Mantle, and Temple Garden, and correctly figure he’s on an equip-the-tree plan. He lays Arbor and passes, and I play another Delver and attack on the ground for 1. My opponent tries to put Rancor on the Arbor with Garden, but I Bolt it in response. The Delvers flip and are joined by a Mandrills, attacking for lethal the turn after. Game 2, I Shoal Spirit Mantle with a 2/3 Tarmogoyf out, growing him to 4/5. My opponent has Gladecover Scout with Ethereal Armor and Hyena Umbra, and asks how big my Goyf is. I say “4” and he attacks with the Scout. I block and he says, “First strike?” I say sure and then eat the Umbra. Guess he didn’t know Goyf had +1 toughness. I scry Stubborn Denial to the top and draw it withGitaxian Probe for life, leaving mana up instead of casting Mandrills and Delver in case my opponent draws a Coronet. He does, and I Deny it before casting my creatures and swinging for lethal.

Game 1, we both mulligan and I lead with Probe, Delver. I see Dryad Arbor, Rancor, Daybreak Coronet, Spirit Link, Spirit Mantle, and Temple Garden, and correctly figure he’s on an equip-the-tree plan. He lays Arbor and passes, and I play another Delver and attack on the ground for 1. My opponent tries to put Rancor on the Arbor with Garden, but I Bolt it in response. The Delvers flip and are joined by a Mandrills, attacking for lethal the turn after. Game 2, I Shoal Spirit Mantle with a 2/3 Tarmogoyf out, growing him to 4/5. My opponent has Gladecover Scout with Ethereal Armor and Hyena Umbra, and asks how big my Goyf is. I say “4” and he attacks with the Scout. I block and he says, “First strike?” I say sure and then eat the Umbra. Guess he didn’t know Goyf had +1 toughness. I scry Stubborn Denial to the top and draw it withGitaxian Probe for life, leaving mana up instead of casting Mandrills and Delver in case my opponent draws a Coronet. He does, and I Deny it before casting my creatures and swinging for lethal.