Are you a Quiet Speculation member?

If not, now is a perfect time to join up! Our powerful tools, breaking-news analysis, and exclusive Discord channel will make sure you stay up to date and ahead of the curve.

In MTG Finance and collecting in general, there are really only a handful of meaningful options that one can exercise at any given time:

- You can buy an item(s).

- You can trade an item(s) for other item(s).

- You can hold onto an item(s) you believe will be more valuable at a later date.

- You can sell an item.

Today's article is about the last action on the list, selling an item, and why the average collector should be more diligent about utilizing this option more often.

But Selling is a Hassle...

Let's cut to the chase. Selling cards is by far the least fun, most difficult, and most tedious of the possible things one can do with one's cards. If you consider the other options – keeping all of one's cards, buying new cards, or trading cards – the prospect of going online and actually selling cards is the one that most feels like work.

Plainly stated, the reason it feels like work is that it is work. With that being said, the work of selling cards isn't actually that difficult, it just takes a little bit of time, energy and effort.

There are plenty of fantastic resources that exists to sell cards in our modern, internet-driven world. eEBay, social media and large online marketplaces are all tools available for turning cards into cash.

The number-one reason I believe that players don't sell as frequently as they should revolves around the inconvenience and investment of time and energy that goes into the process: listing items, processing sales and mailing items.

To be fair, players sell cards all the time. Go to any Grand Prix and observe the endless lines of players at retail booths waiting to sell their cards to vendors. Keep in mind, these players are waiting to sell their cards for roughly half of what they could have gotten if they had done it themselves from home.

If that analogy doesn't make it clear that a relationship between "hassle and convenience" is in play, I don't know what does!

Cash Is So Much More Useful Than Cards

You can't sleeve up $100 dollars bills and play, right? Wrong. Cash is whatever you want it to be whenever you need it to be something (in most cases).

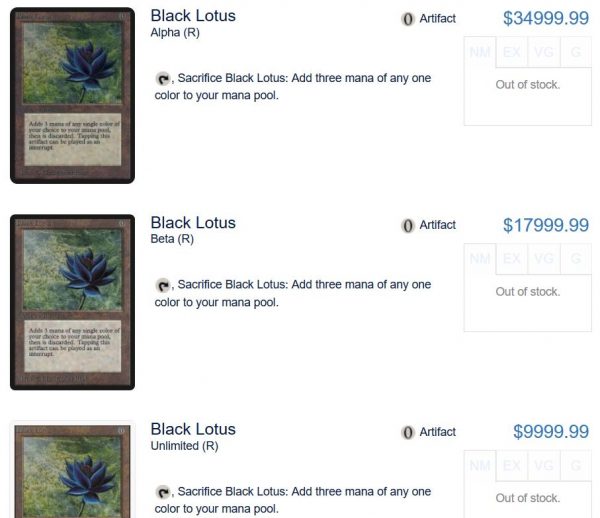

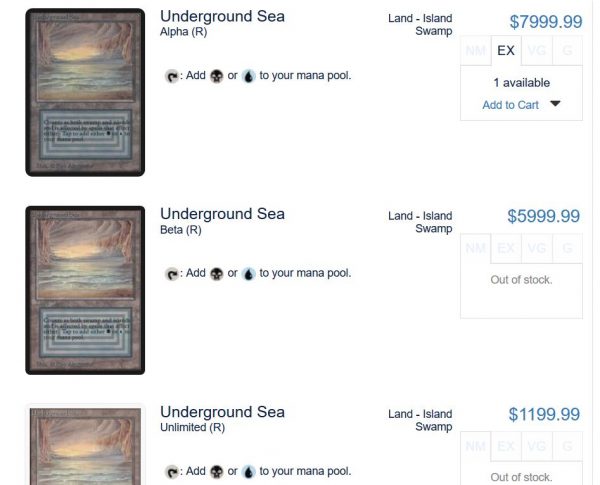

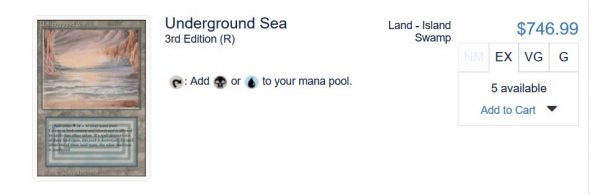

There is clearly a difference between random cards one owns and the cards they have pinpointed as investments. I'd much rather have the Beta Power 9 I bought eight years ago than the money I spent on them in my bank account. Yet for every great investment of funds, there are probably ten cards I own that I missed the window to sell on.

And honestly, most of these missed opportunities have more to do with being lazy and not feeling like listing the card, as opposed to not understanding when was a good time to get out of the card. I think this is especially true of Standard and Modern cards. In a world where reprints influence and dominate what happens in the marketplace, there are not a ton of good reasons to be holding onto these types of cards indefinitely. I'm not advising you to liquidate your entire collection. Obviously, it makes sense to own the cards you frequently, or are likely, to play with.

However, cards that you don't really play with that you are not very likely to play with in the future, really are prime cards to ship out while they still have the semblance of value.

I've been going back through my "cards I want to play" binders for Modern lately and being realistic about whether or not cards I "own" are things that I'd ever play with again. I mean, how likely am I to ever play Elspeth, Knight-Errant ever again? Probably zero percent, since better cards exist now. Why not sell it now while it has some value, as opposed to waiting until it gets reprinted another time and has no value?

Justify the Effort

The biggest way that players justify not spending the time to actually list and sell their own cards directly to the consumer is that it simply takes up too much time. The key is to justify why it is worth time.

Imagine the next time you sell a big stack of cards at a dealer booth. Say you sell about 100 cards and get $250 cash at the booth. Now imagine that, if you had simply spent a couple of hours listing and selling those cards, you would have come away with closer to $500.

Maybe you are a CEO of a Fortune 500 company and your time is worth more than that, but that seems unlikely since you waited in line to sell cards to a dealer. The hourly rate of selling cards online rather than to buylists can be very much worth the effort. The other key is that you can do it in your free time when you'd basically have nothing else to do; it's a great way to turn downtime into additional value.

Personally, I like to sit down and list a few items while I'm on the couch watching Netflix in the evening. I take a playmat and set it on the coffee table and snap a few pictures of the cards I'm looking to sell on my phone. Then I simply upload those pictures to whatever profile I'm selling from. It barely even disrupts my viewing and when done even a couple of times a week creates tons of possible sales.

I also understand that running back and forth to the post office is a hassle. Simply include in your seller profile or description that you take all items to the post office on Tuesdays, and so no matter when the item is purchased that it will ship the following Tuesday. Tuesday morning rolls around and I simply package up everything that sold that week, put it into envelopes, and ship it. Easy earned money.

Selling cards in the retail marketplace is one of the most important ways to make money from investing in Magic. In these articles, when I discuss "selling into a spike," this is exactly what I'm talking about. When I draft some stupid new planeswalker that is selling for $30, I want to get that money and reinvest it into Old School Cards.

Sure, it's nice to try and trade bloated Standard cards for sweet Arabian Nights cards, but realistically, who is going to make this trade with you? It's not like there are tons of random players walking around with Reserved List cards saying, "Will somebody please take these off my hands!? I'm looking for Standard cards that are 100-percent to be worth nothing in three months."

You could sell these cards to dealers and take a small trade bonus and put that credit toward sweet investment cards. If that is the case? Why not just sell them yourself, get a bigger return, and then shop the entire internet for the best price on the card you actually want (rather than paying top dollar from an on-site dealer).

QS is a finance website, so I understand many of the readers are probably pretty adept at doing this. However, if you are not doing this and looking for a way to up your collecting game, I think that being more proactive at actually selling cards at the right times is an absolute must!

How do you streamline your selling processes to minimize time spent? How do you maximize your profits? Share in the comments below.

Continuing the discussion of cantrips, I've gone back and forth on Serum Visions in the list. The original list that I saw on Twitter posted by Jeff Hoogland had no cantrips at all, but that felt a little too clunky for my tastes, and required the deck to play too many lands. I've also tried lists with Opt in the place of Visions. When you boil it all down, the Opt vs. Visions debate is centered around one thing: whether you more frequently flip your Delvers because of the deck manipulation offered by Visions or more frequently need to hold up interaction alongside Opt. I've found that I am rarely using Serum Visions to set up Delver and frequently wanting to wait on my cantrips so I can hold up Mana Leaks, Remands, and Spellstutter Sprites. As such, I am more likely to continue playing Opt in the future.

Continuing the discussion of cantrips, I've gone back and forth on Serum Visions in the list. The original list that I saw on Twitter posted by Jeff Hoogland had no cantrips at all, but that felt a little too clunky for my tastes, and required the deck to play too many lands. I've also tried lists with Opt in the place of Visions. When you boil it all down, the Opt vs. Visions debate is centered around one thing: whether you more frequently flip your Delvers because of the deck manipulation offered by Visions or more frequently need to hold up interaction alongside Opt. I've found that I am rarely using Serum Visions to set up Delver and frequently wanting to wait on my cantrips so I can hold up Mana Leaks, Remands, and Spellstutter Sprites. As such, I am more likely to continue playing Opt in the future.

Two cards have changed since

Two cards have changed since  Chalice of the Void is an interesting spell in this matchup. Rushing it out with Simian Spirit Guide is asking to be two-for-oned by Kolaghan's Command; the Ape is better saved for animating a manland in response to Liliana after tapping out for a fatty. Rather, Chalice's main function is to protect those manlands—and Eldrazi Mimic—from Mardu's heaps of one-mana removal. Blocking Fatal Push for Thought-Knot Seer doesn't hurt, either. Thanks to Command, Chalice doesn't yield a permanent solution, and so should be used as a tempo-gaining tool to push through damage while we can and extract value from our small creatures.

Chalice of the Void is an interesting spell in this matchup. Rushing it out with Simian Spirit Guide is asking to be two-for-oned by Kolaghan's Command; the Ape is better saved for animating a manland in response to Liliana after tapping out for a fatty. Rather, Chalice's main function is to protect those manlands—and Eldrazi Mimic—from Mardu's heaps of one-mana removal. Blocking Fatal Push for Thought-Knot Seer doesn't hurt, either. Thanks to Command, Chalice doesn't yield a permanent solution, and so should be used as a tempo-gaining tool to push through damage while we can and extract value from our small creatures. Our Bolt and Push targets all come out, as well as the Chalices that protect them. Relic heavily disrupts the Bedlam Reveler package and Lingering Souls. Guide is passable thanks to Blood Moon (we can cast it in a pinch), but mostly unexciting post-board, especially compared to what we can bring in. These games go long, and there's no compelling reason to sink extra resources into something that might immediately die.

Our Bolt and Push targets all come out, as well as the Chalices that protect them. Relic heavily disrupts the Bedlam Reveler package and Lingering Souls. Guide is passable thanks to Blood Moon (we can cast it in a pinch), but mostly unexciting post-board, especially compared to what we can bring in. These games go long, and there's no compelling reason to sink extra resources into something that might immediately die. Mardu also has access to some powerful haymakers, although Jose didn't include any in his GP-winning 75. The two we struggle against most are Hazoret the Fervent and Ensnaring Bridge. In want of Dismember, Hazoret can terrorize the game state, pinging us for reach damage and forcing chump blocks or walling our creatures as Mardu solidifies its position. Drawing the Phyrexian removal spell a couple turns later is often too late thanks to the pressure Hazoret applies on its own.

Mardu also has access to some powerful haymakers, although Jose didn't include any in his GP-winning 75. The two we struggle against most are Hazoret the Fervent and Ensnaring Bridge. In want of Dismember, Hazoret can terrorize the game state, pinging us for reach damage and forcing chump blocks or walling our creatures as Mardu solidifies its position. Drawing the Phyrexian removal spell a couple turns later is often too late thanks to the pressure Hazoret applies on its own. This game is less of an arms race than the first in a match against, say, Tron or Valakut, reason being that we've got more relevant interaction here: Dismember answers Scrap Trawler, Chalice on 1 shuts off chunks of the Ironworks engine as well as Ancient Stirrings, and Scavenger Grounds can end their combo turn cold while fizzling a targeting trigger. On top of all that, we're still a Temple-Mimic-Guide-Seer deck.

This game is less of an arms race than the first in a match against, say, Tron or Valakut, reason being that we've got more relevant interaction here: Dismember answers Scrap Trawler, Chalice on 1 shuts off chunks of the Ironworks engine as well as Ancient Stirrings, and Scavenger Grounds can end their combo turn cold while fizzling a targeting trigger. On top of all that, we're still a Temple-Mimic-Guide-Seer deck. Smuggler's Copter also gets the axe, even though it can dig into important cards without fearing removal; sans Reshaper, our pilot density drops, and crewing becomes more difficult. We really don't want to be stuck with a lone Copter against combo, preferring an actual creature to clock them while we disrupt. Reality Smasher would be the next-easiest cut, but its ability to close the window quickly once we land a lock piece is too important here to pass up.

Smuggler's Copter also gets the axe, even though it can dig into important cards without fearing removal; sans Reshaper, our pilot density drops, and crewing becomes more difficult. We really don't want to be stuck with a lone Copter against combo, preferring an actual creature to clock them while we disrupt. Reality Smasher would be the next-easiest cut, but its ability to close the window quickly once we land a lock piece is too important here to pass up. But Ironworks isn't totally out of tricks. For one, they can find Wurmcoil Engine, a card we have a very hard time beating. We can slug through a single Wurmcoil pretty much every game, but when Buried Ruin recurs it, we're in deep trouble. Relic and Grounds get in the way of that plan, but not without leaving us bare to the combo. The best way to beat Wurmcoil out of this deck is to strip it with Thought-Knot or just race; alternatively, creating a big board and pushing through with a Dismember does it.

But Ironworks isn't totally out of tricks. For one, they can find Wurmcoil Engine, a card we have a very hard time beating. We can slug through a single Wurmcoil pretty much every game, but when Buried Ruin recurs it, we're in deep trouble. Relic and Grounds get in the way of that plan, but not without leaving us bare to the combo. The best way to beat Wurmcoil out of this deck is to strip it with Thought-Knot or just race; alternatively, creating a big board and pushing through with a Dismember does it. The sideboard plans in this guide are not set in stone. I encourage you to try different configurations and adapt your decisions based on an opponent's play, as I often do. Rather, the plans presented in this article are examples that aim to give readers a sense of the important and expendable cards in each matchup.

The sideboard plans in this guide are not set in stone. I encourage you to try different configurations and adapt your decisions based on an opponent's play, as I often do. Rather, the plans presented in this article are examples that aim to give readers a sense of the important and expendable cards in each matchup.

However, that may not be possible. The opponent across the table may be living the dream with a completely off-the-wall deck that nobody's seen before. There was no way to prepare for the deck, and now you're completely lost. This is where I've seen a lot of players, myself included, get tilted and give up. It's very dispiriting to be so lost and confused.

However, that may not be possible. The opponent across the table may be living the dream with a completely off-the-wall deck that nobody's seen before. There was no way to prepare for the deck, and now you're completely lost. This is where I've seen a lot of players, myself included, get tilted and give up. It's very dispiriting to be so lost and confused. There are many options for disrupting critical mass decks. Keeping them off their mass is the obvious move, but that isn't always possible; Storm survives Thoughtseize and Liliana of the Veil via Past in Flames, for instance. A stonewall of counterspells is more effective thanks to instant speed, but not without another element.

There are many options for disrupting critical mass decks. Keeping them off their mass is the obvious move, but that isn't always possible; Storm survives Thoughtseize and Liliana of the Veil via Past in Flames, for instance. A stonewall of counterspells is more effective thanks to instant speed, but not without another element. Ideally, it's best to prevent these types of decks from gaining momentum in the first place. This isn't always possible, as for example Ironworks plays cantrip artifacts to find and fuel its combo. Each Chromatic Star popped is a chance to hit and play another one. It's not really possible to disrupt that chain meaningfully. Focus instead on what the deck is lacking, be that a critical piece, mana sources, or even card quantity, and attack appropriately. The timing of disruption is far more important here than against critical mass.

Ideally, it's best to prevent these types of decks from gaining momentum in the first place. This isn't always possible, as for example Ironworks plays cantrip artifacts to find and fuel its combo. Each Chromatic Star popped is a chance to hit and play another one. It's not really possible to disrupt that chain meaningfully. Focus instead on what the deck is lacking, be that a critical piece, mana sources, or even card quantity, and attack appropriately. The timing of disruption is far more important here than against critical mass. These decks can be the hardest to recognize in-game. They don't build to anything, and may not telegraph the combo at all. A deck like Ad Nauseam is mainly cantrips and artifact mana so it does telegraph, but it's an exception. Fair combo decks like Twin or Abzan Company tend to fall under this category, and to the uninitiated, they do not look like combo decks.

These decks can be the hardest to recognize in-game. They don't build to anything, and may not telegraph the combo at all. A deck like Ad Nauseam is mainly cantrips and artifact mana so it does telegraph, but it's an exception. Fair combo decks like Twin or Abzan Company tend to fall under this category, and to the uninitiated, they do not look like combo decks. Of course, identifying the relevant spells can prove tricky. On the surface, only Gifts Ungiven and Past in Flames really matter in Storm, but only countering those cards can leave the door open for multiple Grapeshots with Remand.

Of course, identifying the relevant spells can prove tricky. On the surface, only Gifts Ungiven and Past in Flames really matter in Storm, but only countering those cards can leave the door open for multiple Grapeshots with Remand. could never combo-kill with Deceiver Exarch because every Exarch made was countered by a point of lifegain. Two sisters stopped Pestermite.

could never combo-kill with Deceiver Exarch because every Exarch made was countered by a point of lifegain. Two sisters stopped Pestermite. Magic, and therefore tend to have higher failure rates than non-combo decks. That rate increases the more pressure is applied. Putting the combo deck on the clock and forcing them to win first may yield a win.

Magic, and therefore tend to have higher failure rates than non-combo decks. That rate increases the more pressure is applied. Putting the combo deck on the clock and forcing them to win first may yield a win. While in interactive matchups it is often correct to play around cards, that isn't always possible against combo. Against a decent combo player, it will actually hurt more to play around them than to ignore them. The combo player will go for it at some point, and the later that point is, the more likely the combo is to succeed. Disrupt the combo or race the combo; just don't try and bluff the combo if it impedes your own gameplan. Make your opponent as afraid of your gameplan as you are of theirs, and even against completely unknown decks, you stand a chance of victory.

While in interactive matchups it is often correct to play around cards, that isn't always possible against combo. Against a decent combo player, it will actually hurt more to play around them than to ignore them. The combo player will go for it at some point, and the later that point is, the more likely the combo is to succeed. Disrupt the combo or race the combo; just don't try and bluff the combo if it impedes your own gameplan. Make your opponent as afraid of your gameplan as you are of theirs, and even against completely unknown decks, you stand a chance of victory.